The Survivors of the Survivors: FRF’s First Conference Exceeds Expectations

“Cambodian and Vietnamese Highlander” Conference was held on February 3–4, 2018, at University of North Carolina Wilmington (UNCW)

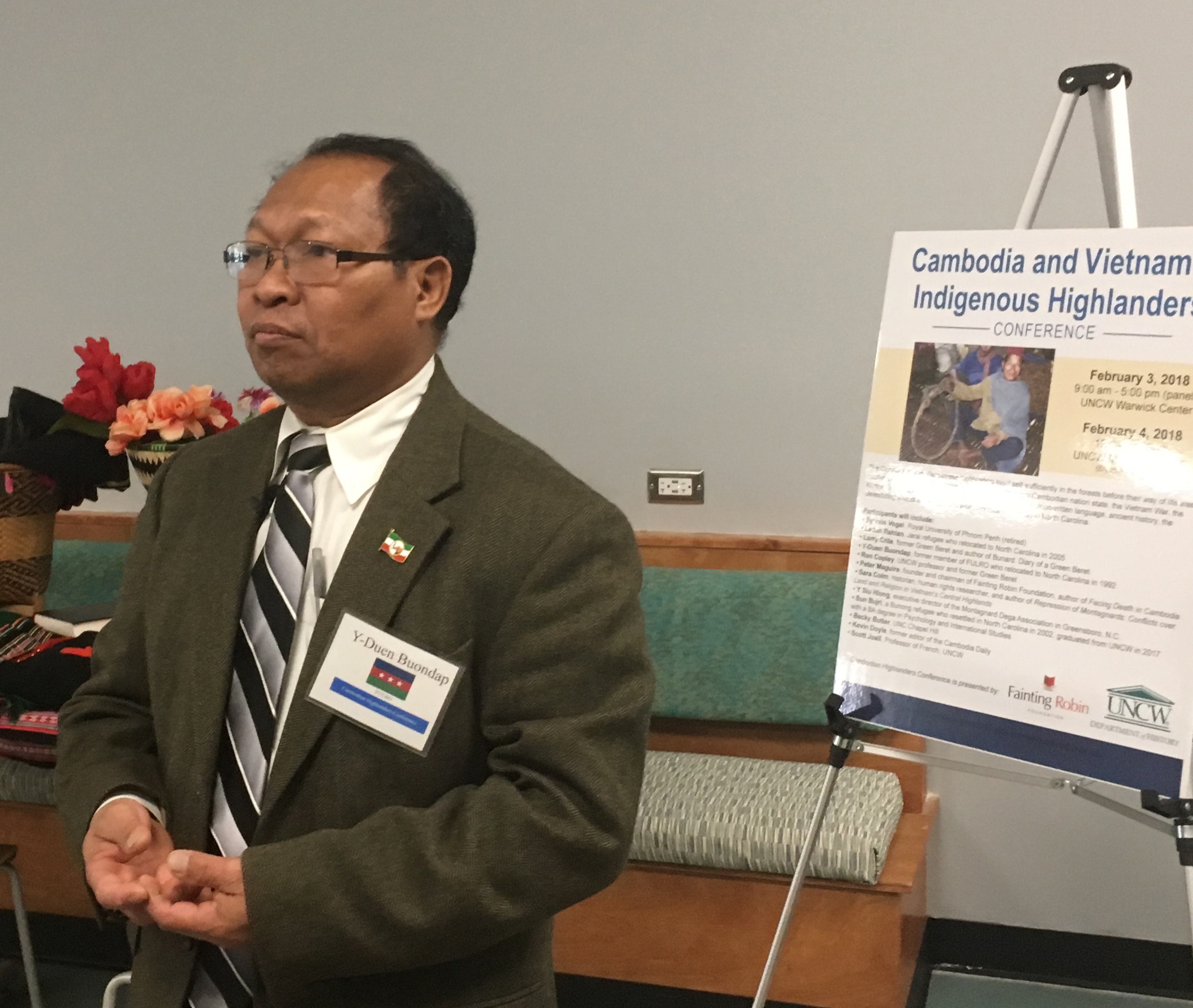

Just before the first panel of Fainting Robin Foundation’s Cambodian and Vietnamese highlander conference began, decorated Green Beret Ron Copley rose and addressed the Montagnards who had traveled from different parts of North Carolina to attend the event. Copley thanked them for their loyalty to U.S. Special Forces during the Vietnam War and added that he would probably not be alive without them. Some in the audience, like Y Siu Hlong and Y Duen Buondap, were once soldiers of the United Front for the Struggle of Oppressed Races, better known as FULRO, a Montagnard resistance movement that sought autonomy from Vietnam. FULRO as well as Montagnards trained by US Special Forces as Civilian Irregular Defense Forces (CIDG) began fighting the Vietnamese during the early 1960s. By the time the U.S. withdrew from Southeast Asia in 1975, 85 percent of Montagnard villages had been destroyed and half of their adult males were dead. FULRO’s remaining 10,000 soldiers continued to fight the Vietnamese after the U.S. withdrawal. Even though 8,000 of their men had been captured or killed by 1979, they launched attacks against the Vietnam troops into the early 1990s. Y Siu Hlong and Y Duen Buondap both thanked the Green Beret for his heartfelt words and told him that they did not blame him for the political decisions that set their people’s tragedy into motion. After this public act of contrition and forgiveness, it was clear to everyone assembled at UNCW’s Warrick Hall that this would not be a typical academic conference.

Few know that today North Carolina boasts the largest population of indigenous highlanders from Vietnam and Cambodia outside of Southeast Asia. Commonly and collectively referred to as “Montagnards,” they number more than one million people in Cambodia and Vietnam and come from more than thirty distinct ethnicities, including Jarai, Ede (Rhade), Bahnar, Bunong, Stieng, Koho, Lach, Sedang, Raglai, Hre, and Bru. In Vietnam, Montagnards were also America’s most valiant allies during the Vietnam War. “We fought alongside them from 1962 until 1973. We loved them. They were a sturdy reliable people. They were brave, and many of them saved many of our lives,” wrote retired Green Beret Jim Morris.

Although U.S. government officials promised to continue supporting FULRO forces even after the US withdrawal in 1975, instead they were abandoned and faced “vae victis” (woe to the conquered). The highlanders were left to face a Vietnamese government not just intent on revenge, they wanted to repopulate the Central Highlands with Vietnamese “lowlanders.” “The Montagnard people and the Americans are like one family,” one of the last FULRO soldiers to lay down his arms told reporter Nate Thayer in 1992. “I am not angry, but very sad that the Americans forgot us. The Americans are like our elder brother, so it is very sad when your brother forgets you.”

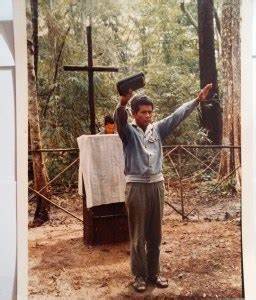

By the mid 1980s, many believed that FULRO had been completely wiped out. Human rights officials and American veterans were stunned when a group of FULRO fighters arrived in a Thai refugee camp in 1986. They had spent the better part of a year eluding Khmer Rouge and Vietnamese army troops, crossing on foot to Thailand. Although they were eventually resettled in North Carolina, the soldiers said that hundreds of their comrades remained in make-shift camps in the remote, malaria-ridden forests of Cambodia’s Mondulkiri Province, . Not only did they live off the land, they also continued to attack the Vietnamese “lowlanders” they so despised. “Here we are free,” one FULRO leader told Thayer. “The communists will not let us pray. They say that Christianity is an American and French religion, so we came to live in the jungle.”

When Thayer found the last FULRO faction deep in the Mondulkiri forest in 1992, he was the first white man they had seen in 17 years. The first thing they asked the reporter, in English no less, was if he had orders or knew the whereabouts of their leader Y Bham Enoul. When Thayer informed them that he had been executed by the Khmer Rouge in 1975, some wept while others refused to believe him. One of the FULRO leaders asked for three things: proof Y Bham Enoul was dead, the arms the Americans had promised 17 years earlier, and a meeting with the American ambassador. “I have a plan for the future, and they should know clearly our position for the revolutionary struggle,” he said. “We want to know whether they will help us or not. The Americans had a whole plan for Indochina.” Before the 398 FULRO soldiers and their families boarded the Russian helicopters that would take them on the first leg of their journey to America, they surrendered 194 old but perfectly maintained weapons, 2,567 rounds of ammunition, and a single M-79 grenade launcher with one round.

Hardest hit by the news that their abandoned comrades were not only alive, but still resisting the Vietnamese, were the American veterans who served with them, especially the veterans of Army Special Forces. In short order, an unlikely alliance of Vietnam veterans, human rights officials, missionaries, reporters, US government officials, and others began working across party lines to get successive waves of highlanders from the jungles of Mondulkiri to North Carolina. Not only did North Carolina’s Vietnam veterans help their former allies gain political asylum, many were there to greet them when they arrived at Charlotte-Douglas International Airport in December of 1992. Don Wolford, an Army Special Forces medic showed one reporter a Vietnam-era photograph of himself with two Montagnards. “These people are our friends. They were very loyal to us,” he said. Veterans, church groups, and others who helped the refugees settle in Raleigh, Greensboro, and Charlotte were amazed by their work ethic and stoicism. “They don’t sit around and brood about how rough it is,” said Margaret Pierce, director of a Catholic refugee relief agency in Charlotte that helped house and teach them English. “They are very smart people and hit the ground running. They are the survivors of the survivors.”

The next waves of refugees came to North Carolina after Montagnards held protests in Vietnam’s Central Highlands in 2001, 2004, and 2008 calling for religious freedom, land rights, and an end to ethnic discrimination. When the Vietnamese government responded with force, thousands of highlander families fled on foot for the forests of Cambodia’s Mondulkiri and Ratankiri provinces. Even though the Montagnards met the terms of the United Nation’s 1951 convention on refugees (any person with a well founded fear of being persecuted for race, religion, nationality, social group or political opinion), the Cambodian government forcibly returned many of them to Vietnam. Once again, the unlikely alliance of Vietnam veterans, human rights officials, missionaries, reporters, and US government officials reactivated their underground railroad to get the highlanders from Cambodia and to North Carolina.

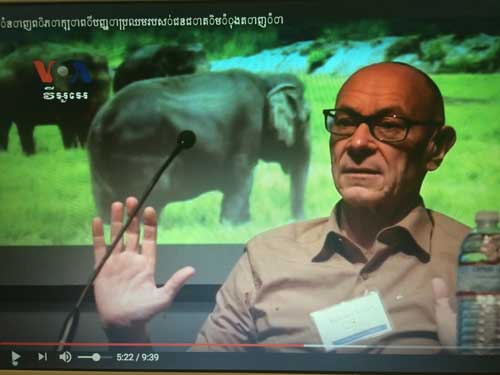

Sylvain Vogel, Fainting Robin Foundation’s 2017 Distinguished Scholar, opened the Cambodian and Vietnamese highlander conference by comparing the highlanders’ vast body of oral literature, once passed down from generation to generation, to Homer’s Odyssey. Vogel believes that the stories are attempts to explain social facts that present anomalies to their society. Vogel, whose work focuses on the Bunong ethnic group, told one of their tales, “The Children Who Were Changed Into Elephants.” In it, two boys senselessly kill one of the god’s water buffalo with their new crossbows and are punished by being transformed into elephants. The moral of the story, don’t kill for the sake of killing, is an idea that is repugnant to the Bunong, renowned for their skills in capturing and raising wild elephants. Vogel has no illusions about the future of the Bunong and other highland groups, and believes that their cultures are on the brink of extinction. That is why the linguist has spent the last 25 years documenting their language and folklore on his own time and at his own expense.

“I offer no solutions. No wishful thinking, no politically correct language, and no bleeding hearts can change a thing,” he explained. “I am only a witness who has watched, with great sadness and a feeling of helplessness, the disappearance of a culture.” The linguist concluded his talk by pointing out that although the highlanders survived decades of war, globalism has proved to be their most daunting foe. Huge old-growth forests of mahogany, rosewood and other tropical hardwoods, once their home and means of sustaining their traditional way of life, are now some of Southeast Asia’s most valuable exports. One point of hope, however, were the many connections Vogel made with members of the Bunong community in North Carolina, as well as historians and linguists here, with whom he hopes to collaborate in future projects of cultural and linguistic preservation.

In the second panel Sara Colm tracked the history of the fiercely independent Bunong in Mondulkiri, whose ancestral territory straddles the present-day Cambodia-Vietnam border. Traditionally, they lived in a network of independent villages, governed by their own inhabitants, where they refused to pay tribute to the Khmer kings. Later, they put up strong resistance to French colonial rule through a series of rebellions that caused the French to lose control over the Bunong in Cambodia for more than 20 years, until the mid-1930s. After independence in 1953, Sihanouk’s forced relocation of highlanders and confiscation of their land fueled more resentment and rebellion by the highlanders, who increasingly joined the Khmer Rouge “forest soldiers” as a more humane and less corrupt alternative to the brutality of Lon Nol’s military and police forces. In 1970, US military advisers convinced Lon Nol to withdraw all troops from Cambodia’s four northeastern provinces, including Mondulkiri, thereby ceding one-quarter of Cambodia’s territory to the Khmer Rouge a good five years before they took the rest of the country. In contrast, the situation of highlanders just across the border in Vietnam was much more chaotic, where different military factions – US forces, ARVN, Viet Cong and FULRO – competed for the hearts and minds of the highlanders, who were caught in the middle. Tens of thousands of Montagnards were displaced from their villages and re-grouped in strategic hamlets or adjacent to Special Forces bases in order to physically separate them from Viet Cong and create free fire zones. Panelist Y Siu Hlong, a member of the Bunong ethnic group and former FULRO soldier, described how FULRO was able to survive in the jungles of Vietnam and Cambodia after 1975, as they waited for the US to come through with their promise of support: “We had thousands of soldiers all over the Central Highlands. We had to move from place to place in order to survive, using guerrilla tactics, sometimes fighting three or four times in one day. We kept looking for signs of the Americans in the forest, such as Winston or Salem cigarettes that meant they’d come back. How did we survive in the jungle? We did not have supply from the United States, not from anyone outside our group. We had no food, no medicine, so we relied on natural resources. We would pick up the wild root, the wild green to eat to survive. For ammunition, we would kill the enemy. From one enemy we would get one weapon and do our best – maybe four or five people would have just one weapon, or just one grenade. We used our minds, our hearts, and our knowledge how to survive. We learned what kind of green to eat if we got sick. What kind of food we cannot eat. It was a very terrible life back then. The Vietnamese would force our family in the village to go with them to search for us. They’d go to the deep river, jungle, with hunting dogs and call to us: ‘Come back son, come back daughter, the government is good, the government forgives you, we won’t put you in jail’.” But it wasn’t that easy to look for us. We knew how to hide. We are military, all our leaders were trained by Special Forces. That’s why FULRO survived for 30 years, and continued to fight without supply. It was a very terrible life.” Now the executive director of the Montagnard Dega Association in Greensboro. Y Siu focuses on helping Montagnard refugees adapt to their new lives in America. “I don’t have any hope that we can liberate or recover our country because no one supplies us,” he said. ”We don’t want to go to war with anyone.” The third panel on the Vietnam War featured Larry Crile (author of Bunard: The Diary of a Green Beret) and Ron Copley, who served together with the U.S. Army’s 5th Special Forces Group in Vietnam and the Montagnard Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) in 1968. Crile, an army medic who delivered 35 Montagnard babies in Vietnam, said that the highlanders never doubted him in the camp’s medical dispensary and he never doubted them in combat. “In the jungle, looking to stay alive, if you hear monkeys raising hell in the treetops,” wrote Crile, “they either saw NVA in the area or got sprayed with Agent Orange. Not necessary to speak ‘monkey’ and ask. In those nervous hours, the ‘baggage’ of language seemed to fade away.” The most important thing he learned in Vietnam came from his Cambodian interpreter, who told him, “You can’t solve an eastern riddle with a western mind.” “Think more with your heart and less with your mind,” his interpreter advised him, “because the mountain people live much more simply and had a sense of appreciation for everything.” Although Crile is saddened by the price the Montagnards have paid since 1975, he is even more saddened by the fact that he “can’t change it.”

Copley told a story about preparing for a night time attack. That night, Crile and Copley slept on opposite sides of a large tree with their M16 in their laps. Each man slept for an hour while the other kept watch for an hour. The two Special Forces men later learned that their two Montagnard bodyguards had also stayed awake all night to make sure the two Americans were not harmed. Copley thanked the Montagnards not just for that night, but for all the days and nights the Montagnards protected US Special Forces men. Ron Copley readily admitted that he would not be alive today if it were not for his Montagnard allies.

The third panelist, Y Duen Buondap, joined FULRO in 1976 and was among the last of their fighters to migrate to North Carolina in 1992. He thanked the U.S. government for saving his life, but added, “We have a dream like the American people of freedom.” The highlander urged the U.S. to force the Vietnamese government “to stop the genocide against our people and to remove them from our land.”

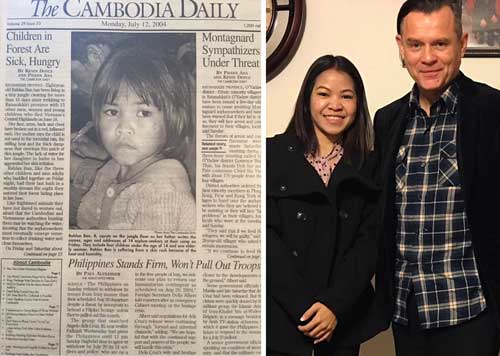

The day’s final panel on resettlement of Montagnard refugees in the US was moderated by Sara Colm, who played an important and unsung role in getting the highlanders refugee status and asylum in the U.S. while serving as Human Rights Watch senior researcher in Cambodia (1998-2011). Colm reminded the audience that even today, Montagnard groups in the Central Highlands are being imprisoned, tortured, and prevented from practicing their religion freely. The panel saw former Cambodia Daily editor Kevin Doyle reunited with Jarai-American refugee Ladhan Rahlan after an eighteen year separation. A photograph taken by Doyle of Ladhan as a malnourished five-year-old hiding with her family in the forest in Cambodia was featured on the cover of the Daily in 2004. It sparked an international outcry that led to the United Nations taking Ladan and hundreds of other Montagnards to Phnom Penh, where they were eventually resettled to the US. Today the small, malnourished girl the reporter met in the forest is about to complete her degree in biotechnology at the University of North Carolina Greensboro. Doyle described how the Montagnard’s plight forced him to confront and cross a journalistic ethical point of no return that changed him forever.

On Sunday the conference screened “This is My Home Now,” a 30-minute documentary film that profiles four Montagnard youth whose families were part of the migration from Southeast Asia to North Carolina. The film was followed by a panel discussion with Sara Colm, Mai Butrang, who was profiled in the film, Phun Bujri, and Theo Rlayang. The three young Montagnards – all members of the Bunong ethnic group -- described their difficult journeys from Vietnam to refugee camps in Cambodia and on to the North Carolina, where they were amazed to be welcomed “like family.” Commenting on the recent tightening of refugee admissions to the US, Phun said: “I feel very heavy when I think about what’s been going on with current refugees and how difficult it is for them to find safety. It’s important to remember that no one chooses to be a refugee, leaving behind their families and their livelihood.” Mai added: “It’s so unfortunate that things have come to this because at the end of the day those people are refugees because they need a home; they need help.”

The weekend conference provided a sobering call for a more realistic and nuanced view of refugees and immigration into the U.S. Many Montagnards have now become U.S. citizens and serve as a living reminder to an American nation with little historical memory. Novelist John Le Carre put it best: “They face us as the living witness of our rhetoric.” In an age where there is a great deal of glib talk about refugees and immigration from both the right and the left, Fainting Robin founder and director Peter Maguire stressed the importance of reflecting on the proud traditions and historical experiences of the oft-forgotten highlander communities in Cambodia and Vietnam. “For me, their fate goes way beyond mere scholarship,” Maguire said. “It is about lost honor, the betrayal of those who risked everything to support America, and above all, the price paid by those who bear arms for the US, be they Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, or Atheist.”

Many of the highlanders in attendance came to North Carolina as child refugees in the early 2000s. Today many are university students and see themselves as the last line of defense against losing what remains of their culture and language. After hearing about this strong desire to learn their language and preserve their culture Fainting Robin Foundation director Peter Maguire and distinguished scholar Sylvain Vogel traveled to Greensboro where they met with hilltribe elders and discussed Vogel returning to North Carolina to teach summer intensives on the hilltribe languages. They also met with officials at University of North Carolina’s Center For Southern History to discuss possible collaboration in the future. FRF’s first distinguished scholar, linguist Sylvain Vogel (see profile below) spent three weeks in the U.S. The Fainting Robin Foundation paid for his travel and all expenses while in the United States. In addition to the conference, Vogel delivered lectures at the UNCW French department, the Center For the Study of Southern History at UNC Chapel Hill and spoke informally at the Montagnard Association in Greensboro, Voice of America in Washington D.C., the Rotary Club of Wrightsville Beach, and to groups in Raleigh and Wilmington.